by malabsorption, and

many patients require

long-term PS1-3

Patients with

SHORT BOWEL SYNDROME

SYNDROME

suffer from

irreparable GI damage and

functional deficiency

of

the intestine1,4

As of 2021, there are ~12,000 patients in

the United States with SBS who are dependent on PS7

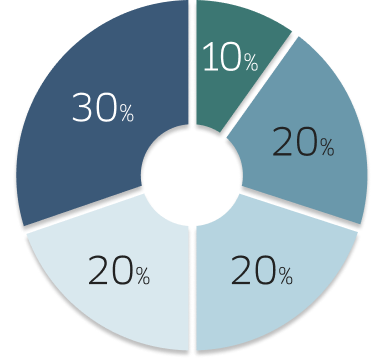

Surgical complications are the leading

causes of SBS in adults8

Main causes of SBS in adults

Remnant bowel anatomy is an important clinical factor

for patients with SBS5

Patients with SBS can be categorized into 3 groups based on remnant anatomy5,8:

End-jejunostomy

Jejuno-colonic anastomosis

Jejuno-ileal anastomosis

SURGICAL RESECTION of the

intestine leads to loss of:

Symptoms of SBS are an everyday concern

for patients3

According to an independent analysis, 50% of patients reportedthey have an accident or leak at least once per week.10

Frequency of accidents or leaks reported by patients with SBS10:

Signs, symptoms, and potential complications of SBS include3,11:

- Malnutrition

- Weight loss

- Drowsiness

- Apathy

- Low body temperature

- Diarrhea

- Confusion

- D-lactic acidosis

- Weakness

- Depression

- Impaired growth and sexual development

- Dehydration

- Difficulty concentrating

- Irritability

- Premature aging

Nutritional, pharmacologic, and surgical

interventions have different roles in managing SBS5,12

Nutritional5,12

- PS provides the essential nutrients and fluids

- Diet modification includes specialized dietary guidance aimed at improving absorption of oral calories and liquid

Pharmacologic8,12,13

Symptomatic management

- Antidiarrheals

- Antisecretory agents (H2 blockers, PPIs)

- Bile acid binders

- Antibiotics

- Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy

- Lactase

Targeted therapy

- GLP-2 analogs

Surgical14

- Intestinal lengthening procedures

- Intestinal tapering

- Intestinal transplantation

Some patients with SBS require LONG-TERM PS to receive

fluids and nutrients necessary for their survival15

According to a survey, patients with SBSspend significant time receiving PS4

Bridge and back 18½ times in the time it takes the average patient with SBS to receive their PS every day.4

Patients with SBS dependent on PS may experience17:

- Catheter-related infections

- IFALD

- Metabolic bone disease

- Thrombosis

- Impaired sleep

- Fatigue

- Depression

- Body image issues

- Disrupted social activities*

- Strain on relationships with family, friends, partners*

*As reported by family.17

Although life-saving, PS can lead to life-threatening complications such as catheter-related bloodstream infections, venous thrombosis, metabolic bone disease, and liver disease.15,17

Sleep disturbances are

Commonly reported by

patients with SBS who are receiving PS4

According to a survey, 2 OUT OF 3 PATIENTS WITH SBS WHO ARE DEPENDENT ON PS

report disturbed sleep as a result of their treatment

The prolonged use of

PS can lead to liver

disease18

PS is supportive management and therefore does not treat insufficient absorptive capacity, which is the underlying issue for patients with SBS who are dependent on PS.3

SBS management

goals include12:

- Decreasing the severity of SBS symptoms

- Minimizing complications associated with SBS

- Reducing long-term PS dependency

REFERENCES —

1. Pironi L, Arends J, Baxter J, et al. ESPEN endorsed recommendations. Definition and classification of intestinal failure in adults. Clin Nutr. 2015;34(2):171-180. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2014.08.017

2. Belcher E, Mercer D, Raphael BP, Salinas GD, Stacy S, Tappenden KA. Management of short-bowel syndrome: a survey of unmet educational needs among healthcare providers. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022;46(8):1839-1846. doi:10.1002/jpen.2388

3. Jeppesen PB. Spectrum of short bowel syndrome in adults: intestinal insufficiency to intestinal failure. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38(suppl 1):S8-S13. doi:10.1177/0148607114520994

4. Data on file. Qualitative interviews of patients with short bowel syndrome and healthcare providers.

5. Iyer K, DiBaise JK, Rubio-Tapia A. AGA clinical practice update on management of short bowel syndrome: expert review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(10):2185-2194.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.032

6. Seetharam P, Rodrigues G. Short bowel syndrome: a review of management options. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(4):229-235. doi:10.4103/1319-3767.82573

7. Ali A, Mitchell G, Gallivan M, Henderson J, Yang M, Iyer K. Epidemiology of patients with short bowel syndrome with intestinal failure (SBS-IF) in the US—findings using real-world data. Poster presented at the AMCP Nexus Conference; October 16-19, 2023; Orlando, FL.

8. Massironi S, Cavalcoli F, Rausa E, Invernizzi P, Braga M, Vecchi M. Understanding short bowel syndrome: current status and future perspectives. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52(3):253-261. doi:10.1016/j.did.2019.11.013

9. Wang CY, Liu S, Xie XN, Tan ZR. Regulation profile of the intestinal peptide transporter 1 (PepT1). Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:3511-3517. Published 2017 Dec 8. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S151725

10. Data on file. SBS patient insights program: digital ethnography study report. Trinity, LLC. August 16, 2023.

11. Nightingale J, Woodward JM; Small Bowel and Nutrition Committee of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for management of patients with a short bowel. Gut. 2006;55(suppl 4):iv1-iv12. doi:10.1136/gut.2006.091108

12. Parrish CR, DiBaise JK. Managing the adult patient with short bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;13(10):600-608.

13. Muff JL, Sokolovski F, Walsh-Korb Z, et al. Surgical treatment of short bowel syndrome-the past, the present and the future, a descriptive review of the literature. Children (Basel). 2022;9(7):1024. Published 2022 Jul 10. doi:10.3390/children9071024

14. Sudan D, Rege A. Update on surgical therapies for intestinal failure. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2014 Jun;19(3):267-275. doi:10.1097/MOT.0000000000000076

15. Ballinger R, Macey J, Lloyd A, et al. Measurement of utilities associated with parenteral support requirement in patients with short bowel syndrome and intestinal failure. Clin Ther. 2018;40(11):1878-1893.e1. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.09.009

16. Jeppesen PB, Shahraz S, Hopkins T, Worsfold A, Genestin E. Impact of intestinal failure and parenteral support on adult patients with short-bowel syndrome: a multinational, noninterventional, cross-sectional survey. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022;46(7):1650-1659. doi:10.1002/jpen.2372

17. Winkler MF, Smith CE. Clinical, social, and economic impacts of home parenteral nutrition dependence in short bowel syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38 (suppl 1):32S-37S. doi:10.1177/0148607113517717

18. Cavicchi M, Beau P, Crenn P, Degott C, Messing B. Prevalence of liver disease and contributing factors in patients receiving home parenteral nutrition for permanent intestinal failure. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(7):525-532. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-132-7-200004040-00003

19. Lakkasani S, Seth D, Khokhar I, Touza M, Dacosta TJ. Concise review on short bowel syndrome: etiology, pathophysiology, and management. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10(31):11273-11282. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11273

20. Mesenteric ischemia - symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic. Published June 2, 2023. Accessed April 11, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/mesenteric-ischemia/symptoms-causes/syc-20374989

21. Bhutta BS, Fatima R, Aziz M. Radiation enteritis. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): Updated August 17, 2023. Accessed May 10, 2024. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526032

22. Kelly DA. Intestinal failure-associated liver disease: what do we know today? Gastroenterology. 2006;130(2 suppl 1):S70-S77. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.066

23. Ashorobi D, Ameer MA, Fernandez R. Thrombosis. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): August 8, 2023. Accessed May 10, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538430

Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | Contact Us

Ironwood® and its three-leaf design are registered trademarks of Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc. © 2025 Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc. All rights reserved.

This site is intended for US healthcare professionals only.

COM-US-NON-0018 v2 01/25